Impact Advisors Group’s Matthew Williams Earns Prestigious AEP® Designation

IAG is proud to announce that Matthew Williams has been awarded the Accredited Estate Planner® (AEP®) designation.

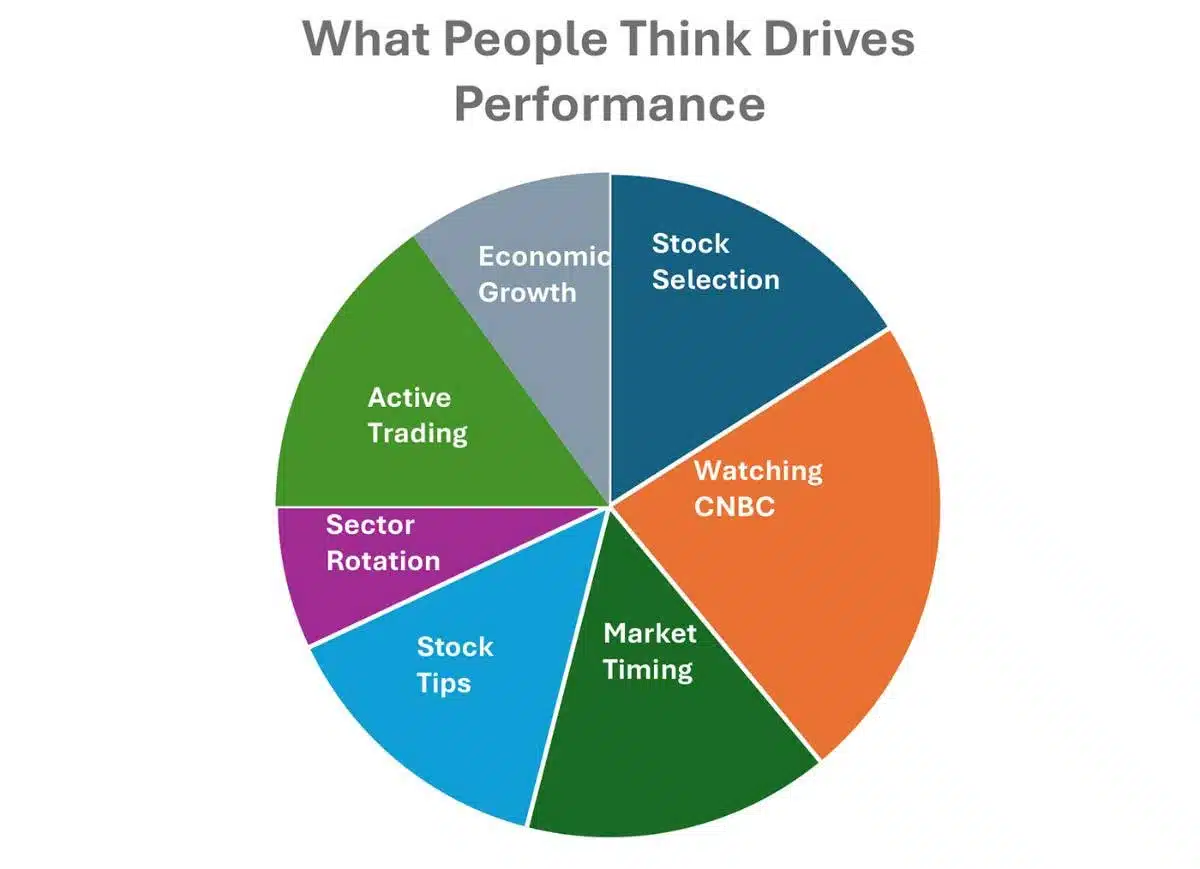

Most investors believe that the cornerstone of an investment portfolio is based upon researching individual stocks and actively trading them. Others believe that getting stock tips, timing the market, or using sector rotation is the key to success. Of course, much of the advertising for brokerage account such as eTrade, or Fidelity, reinforce these misperceptions as active trading is more likely to benefit the broker than the investor.

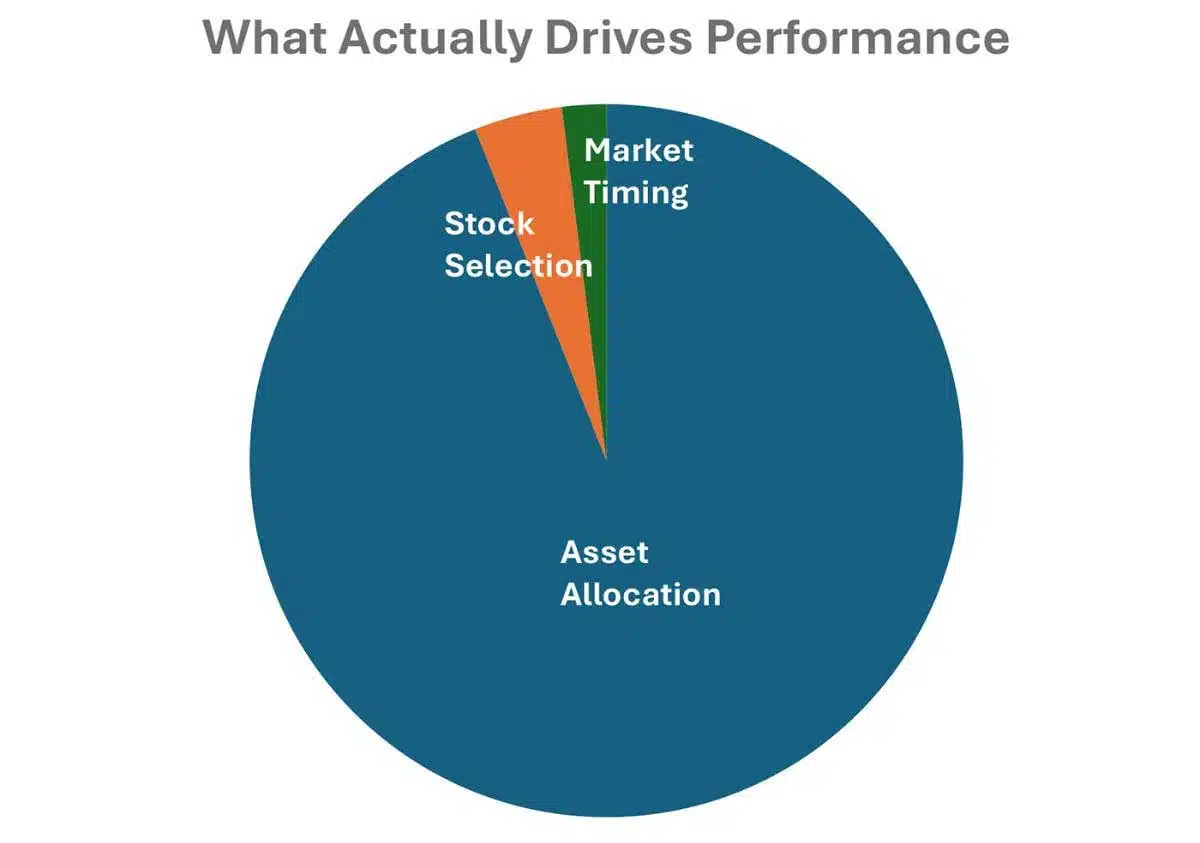

In reality, investing success is overwhelmingly due to creating the asset allocation that matches your risk tolerance, and trading as little as possible except for an annual rebalancing back to your target allocation. The seminal 1995 Brinson, Hood, and Beebower study showed that 93.6% of portfolio returns were explained by the asset allocation. On average, active management actually detracted from returns by about 1% per year.

Studies have shown that active traders underperform buy-and-hold investors by around 1.5 percentage points per year. When Vanguard examined a group of accounts that had superior performance, they found that those accounts had made no changes versus the majority of accounts that traded frequently.

As the economist Paul Samuelson said: “Investing should be more like watching paint dry or watching grass grow. If you want excitement, take $800 and go to Las Vegas.”

IAG is proud to announce that Matthew Williams has been awarded the Accredited Estate Planner® (AEP®) designation.

Many find fulfillment in their work and plan to continue their careers well into their 70s and even beyond.

Against the backdrop of heightened political uncertainty and lower consumer sentiment, investors may have concerns about a recession.

To improve the odds that our business wins long term, it’s essential that we build up our defense against threats, both internal and external.